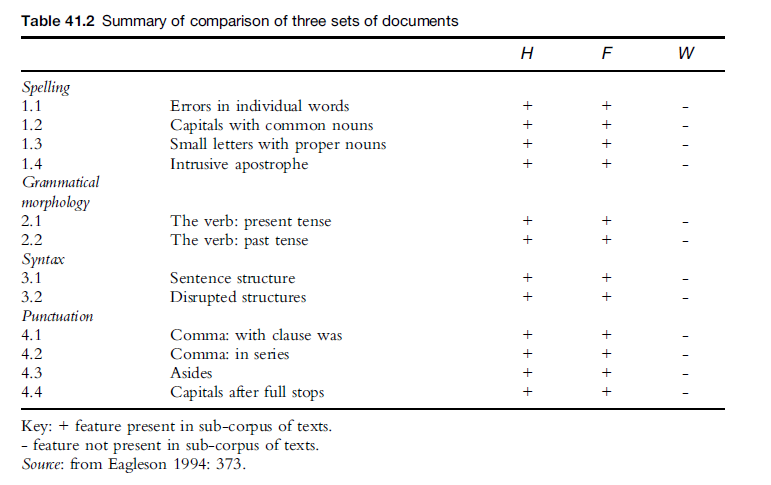

An interesting case is reported by Eagleson in Gibbons (1994), which involved a ‘farewell letter’, apparently written by a woman who had left her husband, but who in fact had been murdered by him. The letter was compared with a sample of her previous writings and a similar corpus of those of her husband. Eagleson concluded that the letter had been written by the husband of the missing woman, and when presented with this compelling evidence the husband confessed to having written it himself and to the murder. The features identified by Eagleson in both the disputed letter and the husband’s corpus of texts included marked themes, the deletion of prepositions and the misuse of apostrophes, as well as grammatical features such as omissions in the present tense inflections and in the weak past tense ending -ed. Table 41.2 is a summary of Eagleson’s analysis: H represents the husband’s corpus, F equals the farewell letter of disputed authorship, and W indicates the wife’s set of texts.

While the majority of forensic work does not yield such startlingly neat results, Table 41.2 gives an indication of the power of using corpora to analyse texts of this type. Had these personal comparative corpora not existed or not been analysed, it is unlikely that the killer would have confessed since he had denied any involvement in his wife’s disappearance until he was presented with the parallel corpora evidence.

It is not only the use of large corpora such as COBUILD or the British National Corpus which enables forensic linguists to contribute to casework. The internet is increasingly being used as a resource for linguistic analysis, although there are certain caveats which need to be applied to its use.

O’Keeffe, A. & McCarthy, M. (2010) The Routledge Handbook of Corpus Linguistics. London and New York: Routledge. (p. 583)