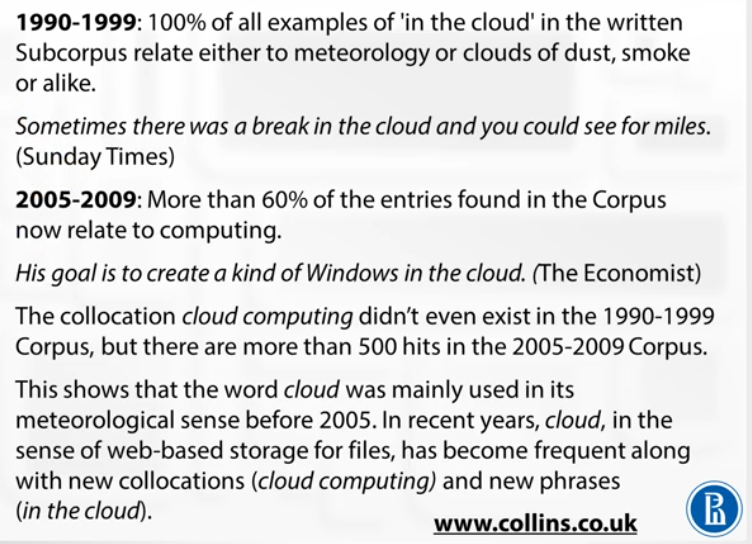

In the cloud

“Languages vary a lot in terms of the information that they pack into a syllable and also in the rate that they are spoken at. But the interesting thing is that the two kind of balance each other, so that more information dense languages are spoken slower, and those that are less informationally heavy are spoken faster. This means that there is a steady information rate that is very similar among languages,” says study co-author Dan Dediu, a researcher at Lyon’s Laboratoire Dynamique du Langage.

A stand-up artist checks his mic before the show, then looks at the faraway bar. There sit a local, a Frenchman, a Mexican and a German.

– Hey guys, can you see me?

– Yes

– Oui

– Si

– Ja

A Georgia student visiting Harvard asks a passing student, “Excuse me, can you tell me where the library’s at?” The Harvard man says, “Here at Harvard, we do not end a sentence with a preposition.” The Georgia boy thinks for a second and tries again: “Sorry, can you tell me where the library’s at, asshole?”

(c) You Are What You Speak (by Robert Lane Greene)

Погрязла в попугаях.

Я более или менее часто встречаю в английском четыре слова для попугая: parrot, parakeet, cockatoo & macaw (в порядке убывания частоты). Попыталась разобраться, кто есть кто; короткое резюме внизу.

.

Parrot – это номинально зонтичный термин, но если им назвать тех, кто попадает в категории parakeet/cockatoo, это вводит людей в заблуждение. Ну типа как плесень – это тоже грибы, но если её называть грибами, вас не сразу поймут.

.

Parakeet – это всякие волнистые попугайчики и прочая малогабаритная заключённая в клетки домашняя живность.

.

Cockatoo – всё, что с хохолком. Точнее, только те parrots, что с хохолком.

.

Macaw – большие дикие яркие разноцветные попугаи типа ара. Это такие штуки размером с предплечье, которые всё равно не спрячутся в джунглях, поскольку постоянно орут, ну значит, можно забить на камуфляж и радовать детей, фотографов и детей фотографов. Macaws можно называть parrot’ами.

.

Короче, parrot – гипероним для всех трёх слов, но реально взаимозаменяемы только parrot и macaw, когда они совпадают в объекте. А называть parrot’ом какаду и волнистых попугайчиков – зашквар. Tak myślę.

.

Короткое резюме для ленивых:

– есть хохолок? cockatoo

– напоминает волнистого попугайчика? маленький? домашний? parakeet

– яркое красно-сине-жёлто-зелёное пятно из Нового Света? macaw

– не знаешь, как назвать? parrot

”Johannes Aavik, the father of modern Estonian, created nonsense words out of thin air for Estonian, of which forty survive in use today.

Another purist, an overzealous Czech, coined a replacement for kren, “horseradish,” because he thought it had been borrowed from German Chren. He didn’t realize that Chren had earlier been borrowed from Czech. (His coinage, morska retkev, was, ironically, a part-for-part translation of the GermanMeerrettich, “sea radish.” It didn’t survive.)”

You Are What You Speak (by Robert Lane Greene)

“Genders may be arbitrary, but Boroditsky found that they can still a ect how people think about things. To test this, she collected a set of words that were masculine in Spanish but feminine in German or vice versa. “Key,” for example, is masculine in German (der Schlüssel), and when asked to describe a key, Germans were more likely to choose words such as “hard,” “heavy,” “metal,” and “useful.” Spaniards, who use a feminine word for “key” (la llave), were more likely to associate it with “golden,” “tiny,” “lovely,” and “intricate.” But this is not German toughness; when Germans have a feminine word, such as “bridge” (die Brücke), they are more likely to describe it as “beautiful,” “elegant,” and “peaceful.” Spaniards, who use a masculine word (el puente), choose words such as “strong,” “sturdy,” and “towering.” More interesting still is that this testing of Germans and Spaniards was done in English. Once a key was associated with masculinity, the prejudice persisted across Germans’ minds even in a foreign language. Boroditsky also found that German painters tend to paint death as a male gure— unsurprisingly, as death is masculine in German. Russian painters make death female, as does their language.”

(c) You Are What You Speak (by Robert Lane Greene)

Who, upon seeing a cake in the office break room, says, “For whom is this cake?” instead of “Who’s the cake for?” Where did this rule come from?

The answer will surprise even most English teachers: John Dryden, the seventeenth-century poet less well known as an early, influential stickler. In a 1672 essay, he criticized his literary predecessor Ben Jonson for writing “The bodies that these souls were frightened from.” Why the prepositional bee in Dryden’s syntactical bonnet? This pseudo-rule probably springs from the same source many others do: the classical languages. Dryden said he liked to compose in Latin and translate into English, as he valued the precision and clarity he believed Latin required of writers. The prepositionnal construction is impossible in Latin. Hence: it is impossible in English. Confused by his logic? Linguists remain so to this day. But once Dryden proclaimed the rule, it made its way into the first generation of English usage books roughly a century later and thence into the minds of two hundred years of English teachers and copy editors.

The rule has no basis in clarity (“Who’s that cake for?” is perfectly clear); history (it was made up from whole cloth); literary tradition (Shakespeare, Jane Austen, Samuel Johnson, Lord Byron, Henry Adams, Lewis Carroll, James Joyce, and dozens of other great writers have violated it); or purity (it isn’t native to English but probably stolen from Latin; clause-final prepositions exist in English’s cousin languages such as Danish and Icelandic). Many people know that the Dryden rule is nonsense. From the great usage-book writer Henry Fowler in the early twentieth century, usage experts began to caution readers to ignore it. The New York Times outs it. The “rule” should be put to death, but it may never be. Even those who know it is ridiculous observe it for fear of annoying others.

(c) You Are What You Speak (by Robert Lane Greene)

to keep up with the Joneses:

to always want to own the same expensive objects and do the same things as your friends or neighbours, because you are worried about seeming less important socially than they are (Cambridge Dictionary)

“соревноваться с Вандербильдихой”